Diagnostic Assessments for Students

Diagnostic Assessments for Students: A Complete Evaluation Guide for Educators and Parents

Diagnostic assessments are tools that gauge a student’s academic skill set. These evaluations pinpoint a student’s strengths or areas where more practice is needed, offering an in-depth understanding of learning needs. Far from the typical classroom tests or quizzes, these assessments provide data that can guide personalized teaching methods, allowing every child to learn at their own pace and in their own style.

Diagnostic assessments are crucial for understanding a student’s specific instructional needs and identifying areas of improvement. The breakdown in understanding comes with the misuse or loose use of the term “diagnostic.” For example, many people consider standardized achievement tests, benchmark tests, and informal end-of-unit tests to be diagnostics. But technically they are not. These other tests measure proficiency against a standard or a particular collection of content. Teachers may be able to make a diagnosis when combining these data points with other known data points for a particular student.

Understanding Diagnostic Assessments

Diagnostic assessments are tools for identifying a student’s specific instructional needs. They surpass traditional tests, offering an intricate analysis of a student’s academic skills and comprising strengths, weaknesses, and areas for improvement—a personalized map for navigating the student’s learning journey. This depth of insight enables educators and parents to tailor instructional approaches to individual learning gaps and drive overall academic growth.

The methodology behind diagnostic assessments involves a comprehensive evaluation of a student’s performance across academic subjects or specific skill/concept areas. Unlike summative assessments, which measure overall knowledge at the end of an instructional unit, diagnostic assessments are ongoing and formative. They uncover areas where a student may struggle and pinpoint the exact nature of those struggles.

The way this is achieved is by drilling down into content or process areas and finding where a student’s instructional point lies. Concepts and skills are learned in order, and knowing how to break the steps apart can be difficult since it requires a deeper understanding of how to teach certain content. An instructional point is defined by thinking of content as rungs in a ladder. In education, this is called the scope and sequence of the content. The breadth of the content is the “scope” and the order in which it is taught is the “sequence.” The actual instructional point is the next rung in the ladder not mastered by the student, whereas all the lower rungs represent skills that have been mastered. There are many synonyms for these points.

The mastery point is the highest point of understanding within a particular scope and sequence of content. In special education, this point is called the present level of the student, or more broadly, the present level of academic achievement and functional performance (PLAAFP). You want to focus your teaching on the skill or concept on the next rung of the ladder or at the next sequence point. This is called the instruction point or zone of proximal development (ZPD). The ZPD is where the student can start learning next with minimal support.

However, diagnostic assessments aren’t just about uncovering weaknesses. They also highlight a student’s strengths, revealing areas where the student excels. Recognizing these strengths, educators can leverage them to positively support the student’s learning journey. The same approach is used. Content and concepts must be evaluated and broken down into teachable units. If the student is advanced, then this advanced content must be dissected to discover where the student should be supported to reach the next level of mastery.

When their purpose is understood, diagnostic assessments provide educators and parents with valuable insights into a student’s learning profile. It goes beyond merely identifying challenges; diagnostic assessments reveal why those challenges exist and offer an opportunity to address them in a laser-focused manner. This proactive approach allows for precise intervention strategies rather than broad solutions that may not effectively meet the student’s needs.

This is where applying the wrong test to a particular situation can hinder a student’s advancement. An example would be trying to teach a student to read increasingly complex passages. Text complexity is called readability. One way to evaluate readability is to determine the text’s grade-level score. Also, many schools use something called Flesch-Kincaid or Lexile for measuring text, passage, or book difficulty. Readability goes up as the average number of syllables go up per word and the average number of words per sentence goes up.

In other words, the words and sentences are getting longer. If an 8th-grade student appears stuck at 6th-grade-level reading passages, why are they failing to comprehend 7th-grade passages? Is it because they can’t decode longer words? Is it because they don’t know the meaning of many words? Or are they reading the sentences and finding themselves unable to process the meaning of the overall passage? This ability to process meaning requires what we refer to as comprehension strategies skills. To be certain of the specific problem, you need multiple tests pulled together to make an analysis.

Thus, understanding the role of diagnostic assessments means understanding the complex nature of teaching individual students. Teaching and learning are complex, and diagnostic assessments are nuanced. Sometimes a test by itself may not be diagnostic, but when combined with other tests or measures, it becomes diagnostic. This in turn will shape the targeted interventions selected for each student. Choose the wrong measures initially–even if they are labeled “diagnostic”–and you’ll be choosing the wrong instructional content.

With an awareness of the potency and nuance of diagnostic assessments in identifying individual learning needs, we now turn our attention to exploring the various types of tests available, each contributing uniquely to a student’s educational journey.

Different Types of Assessments

When it comes to understanding where students stand academically, standardized tests, diagnostic tests, and informal assessments all play pivotal roles. Be aware that there are competing models or frameworks into which tests can be categorized.

Standardized Tests

Standardized tests are structured tools that enable educators to get a clear picture of a student’s academic strengths and weaknesses.

These tests provide consistent, reliable data, making it easier for educators to identify areas of concern and develop targeted instructional plans based on data-driven decisions. They can also be categorized as summative, high-stakes, or accountability tests/assessments. When they have access to standardized information, educators can ensure that their approach is objective and uniform across the board. One example is the end-of-year test given by the state at each grade level in subjects such as Math, English Language Arts, and Science.

The test provides a summary for the principal of how the school is doing overall, or a way for a district administrator to compare performances between schools. Benchmark tests are another example. They are typically tied to curriculum units or periods of time. For instance, a district may test all students quarterly during the year. They test students only on the math materials that are supposed to have been taught and mastered at each grade level. So the “benchmark” advances each quarter.

End-of-unit quizzes are also standardized when the entire class takes the same quiz because they all just finished the same chapter in a math book used by a particular grade-level class.

The key benefit of standardized tests lies in their ability to provide a uniform benchmark that can be compared across multiple students or schools. By offering a standardized approach to assessment, these tests establish a common ground for understanding students’ academic abilities. This allows educators to identify broader trends within school populations or geographic regions, facilitating more far-reaching interventions and improvements in educational systems. However, it’s important to remain mindful of potential biases or limitations such as test-taking anxiety or cultural factors that may impact a student’s performance. Also, school and district administrators tend to overly rely on these tests since this is the type of information they need–i.e., broad test data. Problems arise when standardized tests push out diagnostic tests that the teacher needs to figure out how to help each student.

Formal Diagnostic Tests

Typically, diagnostics are a collection of tests that combine to provide insight into a student’s individual needs. This combination of multiple data points makes the tests diagnostic. Some are also very specifically designed. For example, the DORA Phonemic Awareness assessment was designed to examine how students break apart audio: can a student hear the /a/ sound in the word “cat” when it is spoken, for instance?

The assessment adaptively reviews nine different types of tasks, all involving audio processing. Would you give this test to a 1st or 2nd-grade student who is learning to read successfully and is at grade level? Probably not. But what if you noticed a student who was not able to learn the expected scope-and-sequence phonics skills? Other students had learned their beginning sounds and then short-vowel phonics principles.

If the struggling student was an English language learner, this might explain the issue. Other languages may have other sounds for the same Roman-alphabet letters. But if the student was not an English language learner and was learning sight words successfully, yet struggling with phonics principles, I would want to test the student’s auditory processing.

Another diagnostic assessment could be used to try to understand why a 6th or 9th grader is struggling in math. Unfortunately, few diagnostic tests exist at these grade levels. Tests may identify some general areas of weakness, but they seldom drill down to find just where to start support. The ADAM assessment covers 44 sub-tests, each with its own scope and sequence. But what makes this test diagnostic is that it adapts up and down K to 7th-grade items. A 6th-grade benchmark test may have items that span the same 44 sub-tests in math, but since it doesn’t adapt up and down, it isn’t finding out exactly where to remediate the student. For instance, on a grade-level benchmark test, a student may miss items in the sub-tests of fractions, decimals, and division of whole numbers. But where does the teacher start to help the student? 6th-grade fractions is a complex subject. Maybe the student’s instruction point is “recognizing numerators and denominators,” which is taught at the 2nd-grade level. Test developers who create benchmark tests like to call their tests diagnostic because they identify the main areas of focus. In this case, those areas are fractions, decimals, and division of whole numbers. But where exactly in the scope and sequence of each sub-test does the student’s instruction point fall?

Informal Tests or Assessments

On the other hand, informal assessments consist of work samples, end-of-unit tests, and observations conducted within the classroom environment. These assessments provide a more flexible and holistic approach to gauging student performance. Together they are diagnostic, because they drive the teacher’s understanding of how to support each student as data points are combined to reach a conclusion or diagnosis.

Informal assessments offer valuable day-to-day insights into student progress and comprehension. They are more granular, which can be helpful. Through observation and work samples, teachers can gain a more complete understanding of each student’s learning process. This allows them to develop personalized instructional strategies that cater to each student’s unique needs and learning style.

For instance, an informal reading assessment might involve observing how a student approaches reading tasks independently, analyzing which words they struggle with, and noting any patterns in their decoding skills. This up-close observation provides nuanced insights into the student’s reading abilities beyond what standardized tests may reveal. Additionally, informal assessments are flexible enough to be tailored to specific classroom goals and learning objectives.

While standardized tests provide consistent datasets for cross-comparison and trend analysis, informal and diagnostic assessments offer the flexibility and context-specific insights that more directly support personalized instruction tailored to individual students’ needs. Diagnostic assessments are often pre-made tests that combine multiple measures to help with student analysis. Informal assessments are given by the teacher, who combines them to make them diagnostic and to allow for a prescription to be formulated. All types of assessments bring tremendous value to the diagnostic process when used in conjunction with each other to create a well-rounded view of student performance.

Understanding the different types of diagnostic assessments sets the stage for exploring their impact on student learning.

The Impact of the Diagnostic Process on Student Learning

Diagnostic and informal assessments significantly improve student learning outcomes, playing a pivotal role in shaping students’ academic journeys. These assessments offer insight into an individual student’s academic profile, enabling educators and parents to understand the student’s unique strengths as well as areas that need improvement. They are the next step in teaching and learning. The difficulty, of course, lies in choosing the right diagnostic tool for the specific situation. Therefore, it is important to understand the nuances of the diagnostic process, which includes familiarity with educational terms that are frequently employed. Below are some expressions often used in the student learning process. It is important to understand what they mean and how testing and diagnosis affect them.

Personalized instruction tailors learning to the individual student’s needs, preferences, interests, and pace. It focuses on the unique needs of each student, often using technology to facilitate this individualized approach. Here are some key characteristics:

- Student-Centered Focus: Learning plans are based on the student’s strengths, needs, interests, and goals.

- Flexible Pace: Students move through the curriculum at their own pace, which allows them to spend more time on challenging areas and less time on concepts they grasp quickly.

- Choice: Students often have choices in their learning paths, including the types of activities they engage in and how they demonstrate their learning.

- Technology Integration: Technology plays a significant role in personalized learning, with tools like adaptive learning software that adjusts to each student’s learning level.

- Teacher’s Role: The teacher acts as a facilitator or guide, helping to create individual learning plans and providing support as needed.

- Assessment, Formal and Informal: These assessments could be as simple as a question or survey to discover students’ interests, styles of learning, and more, or they could be quizzes to find out a student’s academic level.

Differentiated instruction is a teaching approach that involves modifying the curriculum and teaching methods to address the varied learning needs of students in a classroom. It aims to provide multiple paths to learning so that all students can access the same curriculum. Key characteristics include:

- Flexible Grouping: Students are grouped and regrouped based on their learning needs, interests, or readiness for a particular task.

- Varied Teaching Methods: Teachers use a range of instructional strategies and materials to teach the same content in different ways. The strategies can include different levels of difficulty, varied teaching styles, and multiple formats for presenting information (e.g., visual, auditory, kinesthetic).

- Content, Process, and Product: Differentiation can occur in three areas:

- Content: What students learn (varying the complexity)

- Process: How students learn (using different activities)

- Product: How students demonstrate what they have learned (offering choices in assessments)

- Ongoing Assessment: Teachers continuously assess students’ needs and progress to inform instruction and make adjustments as necessary. These assessments can be formal or informal tests, surveys, or quizzes. Collectively, the data allows the teacher to diagnose students’ abilities and adjust as needed.

Teacher’s Role: The teacher proactively plans and implements different approaches to learning within the same classroom to accommodate all students.

Early intervention refers to a range of services and supports provided to young children who have developmental delays or disabilities, as well as to their families. The goal of early intervention is to address developmental issues as early as possible to improve outcomes in various areas such as cognition, physical development, communication, social/emotional development, and adaptive skills.

Here are some key characteristics of early intervention:

- Age Range: Early intervention services are typically provided to children from birth to age three, although some programs extend to age five.

- Developmental Focus: The services target developmental milestones across several domains, including motor skills, cognitive skills, language and communication, social-emotional skills, and self-help/adaptive skills.

- Family-Centered Support: Interventions often involve the family, recognizing the critical role of parents and caregivers in a child’s development. Family training and support are integral components.

- Multidisciplinary Approach: Services are provided by a team of professionals from various disciplines such as special education, speech and language pathology, occupational therapy, physical therapy, psychology, and social work.

- Individualized Plans: Services are tailored to each child’s unique needs, often documented in an Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP). This plan outlines the child’s current levels of development, the specific services to be provided, and the desired outcomes.

- Natural Environments: Interventions are usually provided in the child’s natural environments, such as the home or child-care settings, to promote generalization of skills.

- Screeners and Assessments: Early identification of developmental delays or disabilities through routine screenings and comprehensive assessments is essential. Many school districts have processes in place to make early identifications. But parents should also know about these options, especially for students who have yet to start school.

Analyzing Results from Diagnostic and Informal Assessments

The process of analyzing assessment results can be as revealing as the assessments themselves. It’s not just about looking at numbers but about understanding what those numbers mean for each individual student. By diving into the data, educators and parents can pinpoint specific areas where students are struggling, excelling, or improving. This personalized insight is crucial in tailoring effective teaching strategies and providing the necessary support.

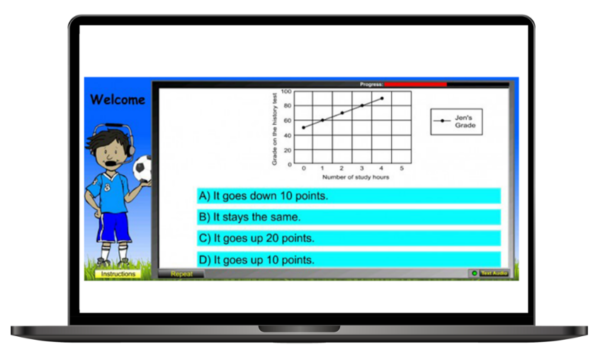

When analyzing results, it is important to look for patterns or recurring errors that may indicate a deeper issue. For example, if a student consistently struggles with a specific type of math problem, it could reveal a fundamental gap in understanding that needs to be addressed. But it is also important to look at other skills or content areas that might affect the student’s difficulty with the math problem. Similarly, discovering consistent strengths in certain subjects or skills can inform decisions about how to further challenge and engage the student.

Imagine a diagnostic assessment revealing that a student is consistently having trouble understanding the main ideas of passages in language arts. This insight allows educators to create individualized learning plans designed specifically to improve the student’s comprehension strategy skills through explicit instruction and support. By identifying these specific learning gaps, the teacher is able to provide focused assistance and intervention tailored to the student’s needs.

To use a different analogy, just as doctors’ test results help them identify health issues and prescribe the most effective treatment plan for a patient, educators and parents can use assessment results as vital tools in designing specialized learning plans for students. This tailor-made approach ensures that each student receives the precise support required for their educational development.

However, tests need to be constantly reviewed for bias. In the example above, in which the student failed to understand the main idea of passages when reading, what if you choose a topic that the student really liked? If the student was interested in food, how might they do when given passages on food-related topics? Similarly, what if the student came from a lower socio-economic background and was accustomed to a different vocabulary from the one often used in academic settings? When the student encounters passages of 7th and 8th-grade difficulty and above, it is worth asking whether vocabulary could be preventing the student from demonstrating mastery of the “main idea” questions in these passages.

Test bias is a very complex topic and many teachers and parents are not trained in identifying it. Test developers may also be guilty of not disclosing their tests’ biases. The Lexile readability score is a ubiquitous leveling system that can be applied to almost any type of text. But just because a student scores at a low level doesn’t mean that student is a poor reader. As mentioned above, if someone has a less advanced vocabulary, their comprehension may appear low. They may be great at decoding and have mastered all the phonics principles but still test low on readability.

This means that it is important to understand the assessment you are using thoroughly and up front. Then, as you continuously assess and monitor student progress, your evaluations will be more effective and will drive the correct interventions and instructional approaches. This ongoing analysis enables educators and parents to make timely adjustments, ensuring that their efforts remain closely aligned with students’ evolving needs.

Understanding the Big Picture of Diagnostic Testing

Diagnostic testing is an essential component of an effective educational strategy, providing valuable insights that enable tailored instruction and targeted interventions. The intricate process of analyzing diagnostic and informal assessments reveals each student’s unique academic profile, guiding educators and parents in developing personalized learning plans. By leveraging diagnostic data, educators can address specific learning gaps and reinforce areas of strength, thereby enhancing overall student outcomes.

However, the successful application of diagnostic assessments hinges on the correct choice and combination of tests. As highlighted, misapplying tests or misinterpreting their results can lead to ineffective instructional strategies and hinder student progress. The use of summative or accountability assessments in lieu of diagnostic tests can be detrimental to student outcomes. Therefore, educators must have a comprehensive understanding of different assessment tools, their purposes, and their potential biases.

In conclusion, diagnostic assessments, when used correctly, serve as powerful tools that go beyond merely identifying academic deficiencies. They provide a nuanced understanding of each student’s learning needs, facilitating precise and effective educational interventions. By integrating diagnostic assessments into a holistic teaching approach, educators and parents can support all students in reaching their full potential, ensuring a more equitable and effective educational experience for all.

Leave A Comment