Special Education

Assessments & Instruction

The IDEA Act and Special Education Policies

One of the key foundational concepts of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) is that every child identified as having a disability is provided with “free appropriate public education that emphasizes special education and related services designed to meet their unique needs and prepare them for further education, employment, and independent living” (IDEA Act). Generally speaking, during an initial evaluation process, identified students are given standardized and alternative assessments in a number of areas, including intellectual performance (IQ test), behavior, autism, learning disability, cognitive disability, speech, dyslexia, and attention deficit, to name a few. These assessments are generally given once in a student’s life in the special education process to determine eligibility. Every three years, the IEP committee can call a team meeting to decide whether to re-assess a child, though this is not very commonly done.

Table of Contents

- Diagnostic vs. Formal Assessment

- Specially Designed Instruction (SDI)

- SDI and Formative Assessment

- Coaching Special Education Teachers During COVID-19

- Evaluation to Coaching

- Technology and a New Paradigm

- Equity and Disproportionality

- Providing FAPE During COVID-19

- Present Levels, Annual Goals, and Diagnostic Data

- IDEA Backgrounder

- Special Education

- The Six Pillars of IDEA

- Individualized Education Programs (IEPs)

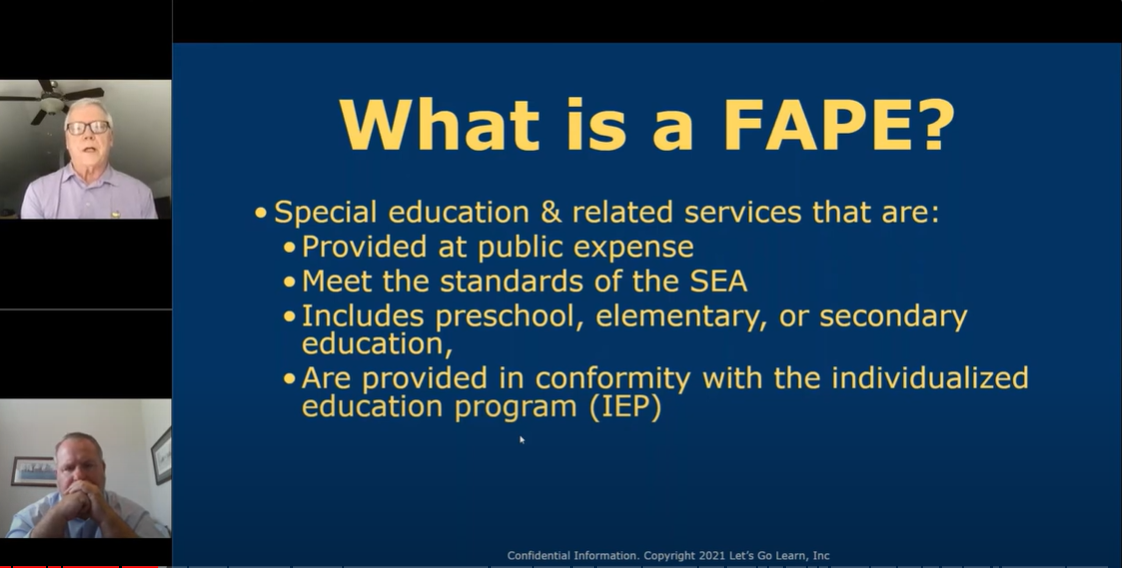

- Free and Appropriate Public Education (FAPE)

- Least Restrictive Environment

- Appropriate Evaluation

- Parent and Teacher Participation

- Procedural Safeguards

- Confidentiality of Information

- Destruction of Information

- Transition Services

- Summary

- Bibliography

Adaptive Diagnostic Assessment vs. Formal Assessment in Special Education

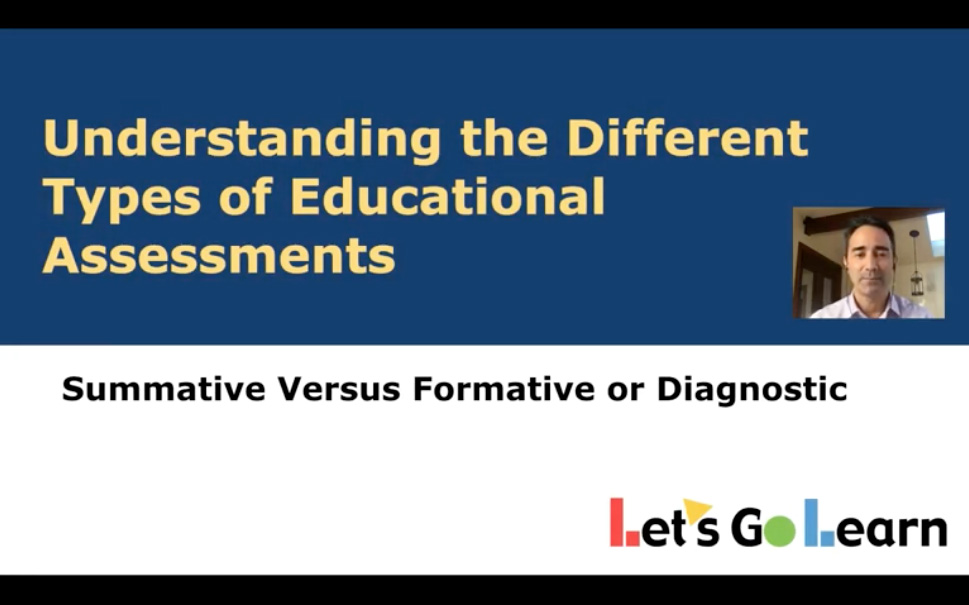

To ensure that a special education program is effective for all students with disabilities, the IDEA Act requires schools to monitor progress toward the annual goals described in the IEPs of students with disabilities. So how do we measure the ongoing progress of children with disabilities toward these goals? Historically, we have used teacher-made tests, quizzes, instructional materials, and classwork to determine progress. This is problematic, however, because these teacher-made measures are not designed to be psychometrically valid, reliable, or equivalent for progress monitoring purposes. The 2017 Endrew F. Supreme Court Case placed heightened focus on the importance and requirements of progress monitoring, so it is important to review which assessments are appropriate.

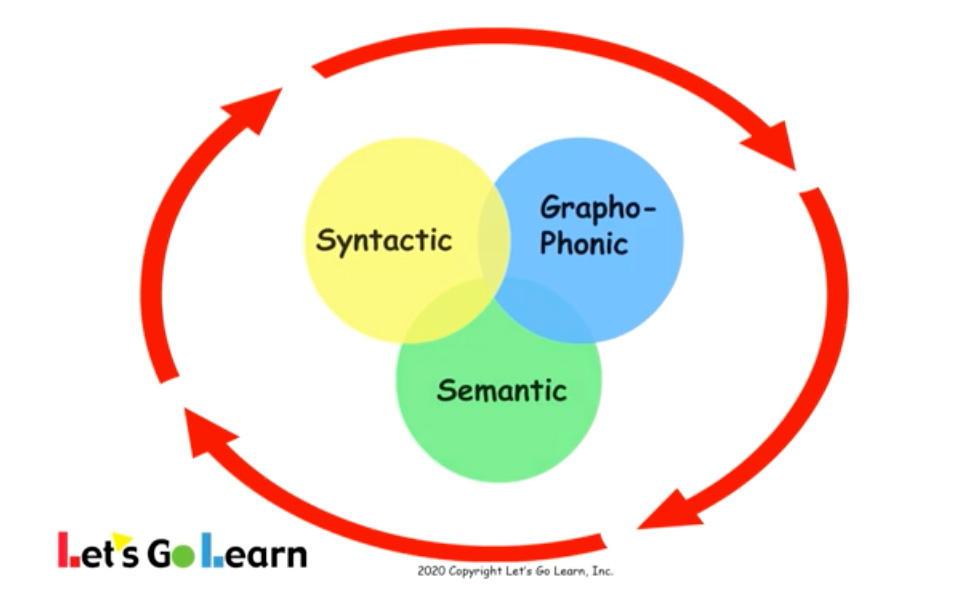

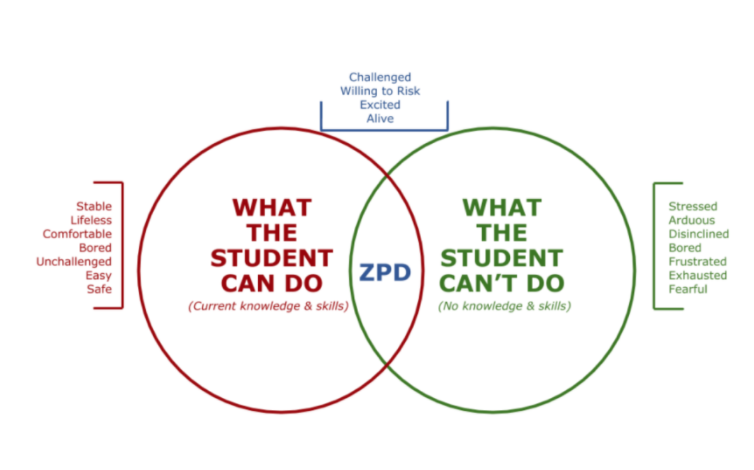

Fortunately, a growing field of assessments is being designed to monitor student progress toward annual IEP goals. These assessments are generally referred to as adaptive diagnostic assessments and are delivered via tech-based platforms and online environments. They allow classroom and online teachers to collect valid and reliable data on students both quickly and accurately. When designed correctly, a true adaptive diagnostic assessment’s difficulty level adapts to a child’s performance to determine their zone of proximal development (ZPD). This means the online assessment system will figure out where the child is performing relative to grade-level content. For example, a child in the fifth grade may be reading at a third-grade level with consequent challenges in vocabulary, comprehension, and phonemic awareness. An adaptive diagnostic assessment will quickly determine the student’s strengths, weaknesses, and grade-level placement. In addition, its system should be able to provide quick and reliable formative assessments that measure overall progress toward annual academic goals.

However, not all diagnostic assessments are equal. Educational publishers often oversell their diagnostic assessments by promoting their use for all students. But for use with students with IEPs, diagnostic assessments need to fully adapt to find a student’s ZPD. A pitfall to avoid is adoption of a grade-level designed “diagnostic” assessment selected for general education students and used for students with IEPs. Special review or consideration is necessary to ensure that it can help meet the IDEA goal.

Specially Designed Instruction (SDI): Definition and Best Practices

One of the most important legal tenets of the IDEA Act is the provision of specially designed instruction (SDI) that meets the unique needs of students with disabilities in elementary school, middle school, and secondary school. It’s not enough for a school to provide an extra aide or classroom teacher in an inclusion environment. Sitting in the back of a regular classroom and waiting to answer questions now and then does not meet the spirit or the letter of the IDEA’s legal requirement. The IEP team must accurately diagnose and pinpoint the current needs of children with disabilities, including physical disabilities, developmental disabilities, language disorders, or communication disorders. Without providing SDI in a meaningful and measured manner, a student is receiving little more than general education instruction.

How do you define SDI?

Roll over to seeSpecially Designed Instruction (SDI)

SDI is defined by the IDEA as follows:

“(3) Specially designed instruction means adapting, as appropriate to the needs of an eligible child under this part, the content, methodology, or delivery of instruction—

(i) To address the unique needs of the child that result from the child’s disability; and

(ii) To ensure access of the child to the general curriculum, so that the child can meet the educational standards within the jurisdiction of the public agency that apply to all children.”

SDI is really about providing instruction in the most relevant form and manner to address the unique needs of the learner. But how does one determine the starting point: which content to teach first, or the child’s needs in general? Performance data from a well-designed adaptive diagnostic assessment can immediately pinpoint the child’s ZPD so that teaching can begin from that point. If classroom teachers are not aware of a child’s strengths and weaknesses, they will not know where to begin, what to emphasize, and what to avoid. The same data used to determine the ZPD and drive SDI should be used to populate the present level of performance (PLAAFP) and set baselines for annual goals.

A powerful process for reaching students who need intensive intervention (Tier 3 in RTI and MTSS) is data-based individualization (DBI). The process begins with diagnostic assessment data from a research-based assessment such as Let’s Go Learn’s DORA or DOMA, which evaluates a content-specific area of concern. The diagnostic data drives the implementation of a validated intervention, such as Let’s Go Learn’s Math Edge or ELA Edge. Frequent progress monitoring with formative assessments that re-align the intervention to current student performance ensures the effectiveness of DBI.

It is essential that the key elements of the IEP are “connected” by data and fused together. The primary pieces of the IEP should fit together just as pieces in a puzzle do. Each piece makes sense when combined with another, coming together to create a clear picture of the child’s educational needs, performance, and progress.

SDI and Formative Assessment

One of the most critical elements of providing quality SDI is ensuring a means of progress measurement and intervention. Teachers, school staff, and parents must respond to the data. As the learning of the child ebbs and flows, so too must teachers and their tools adapt to the child. Therefore, in order to implement quality SDI, a solid formative assessment plan must be in place. This plan is a legal requirement under the U.S. Department of Education, the IDEA Act, and as reinforced by the Endrew F. Case, and the only way to know how and when to adjust an instructional model and approach is by progress monitoring. In addition, quality progress monitoring is the only way to ensure precise measurement of each annual goal.

Currently, public education is not particularly adept at using formative assessment. Even when we do collect information and the data shows negative results, we rarely change our approach. While our education system tends to be good at the basic compliance level of measuring progress and providing some form of SDI, it is far from reaching the spirit of special education initiatives.

At the end of the day, we don’t want educators recording data for recording’s sake; we want them to react and respond to the data. If a child demonstrates marked improvement, then we want to continue with our current practices — and possibly increase the amount of time the services are provided. Conversely, if a child is not making the desired progress, we must shift gears and assess our instructional methodologies. We must make changes when the data necessitate that we do so! Unfortunately, most special education assessment platforms do not have the capacity to implement adaptive formative assessments.

Educators must look hard to find assessments that include both full diagnostics and smaller “chunked” assessments for progress monitoring purposes. In addition, these issues are compounded by the current status of COVID-19 and overall lack of training in ongoing formative assessment. As a special educator and principal, I was never provided with training or support in the area of progress monitoring systems. We must focus on coaching teachers, rather than delivering edicts and directives. We must do a better job of training and supporting our special education teachers and administrators in relation to special education processes and procedures.

Coaching Special Education Teachers During COVID-19

How on earth do we coach and support teachers who are teaching (alone) from their homes? It’s as difficult a question to answer as it is to conceptualize. For most districts around the country, the answer is simply that they won’t do it; during school closures, this kind of coaching is low on the priority list. Furthermore, many administrators express that even if they wanted to do it, they wouldn’t know how to go about it in a remote learning environment. At the beginning of the crisis, many people believed that the school closures were short-term at worst. Initially, schools closed for a few weeks, but now closures have extended to several months. Moving forward, whether schools use a hybrid model or some other configuration of the traditional school day, we must figure out how to support teachers in this new learning environment. Remote learning should not become synonymous with a lack of support for teachers. Rather, we could make this difficult time an opportunity to move teacher evaluation ahead light years by embracing technology and adopting a more coaching-oriented approach.

Special education teachers are at greater risk of isolation and in even greater need of support than their regular education peers; they face daunting realities as they not only try to educate children with a variety of physical and cognitive disabilities remotely but are also tasked with adhering to far-reaching IDEA-related policies and guidelines that were not built for COVID-19. Special education teachers are trying to meet the educational needs of each unique learner from afar while also meeting compliance and regulatory expectations that are accompanied by extensive paperwork during uncertain times. In addition, many special educators have recently come to the field with limited experience or training and alternative licensure.

To add insult to injury, most administrators have very limited experience with special education and are unable to offer meaningful support to their neophyte special educators. Historically speaking, special educators have been on their own island and have had to fend for themselves. Now the situation has grown dire and something must change, or there may be an even greater shortage of special education teachers in the fall of 2021.

One could argue that putting special education teacher evaluation and coaching at the bottom of the pile is the absolute last thing the teacher needs. At no other time has there been a greater need for special education teacher support and coaching than now. Special educators are more exhausted, confused, and isolated than at any other time in the history of American education.

We often misinterpret the evaluation process as one meant to be top-down, didactic, solely evaluative, and perfunctory at best. The truth is that the evaluation process is supposed to be about support, coaching, and helping educators get better. Historically speaking, we have completely missed the boat on the teacher coaching front — particularly with special educators. What we do in schools today is often little more than a glorified checklist with minimal to no beneficial coaching. We provide a few “glows” and a “grow,” mark the teacher as at least proficient, have a brief discussion about the checked boxes, and move on to the next teacher. This evaluation process is contributing to teacher burnout, a reluctance to join the profession, and massive teacher shortages nationwide. A potential silver lining to the COVID-19 era is that it is forcing our cheese to be moved. As educators, we are being forced to do things differently and think outside of the box. Now is the time to reexamine and change how we support special education teachers.

Evolving our Mindset and Vocabulary: Evaluation to Coaching

There is an important difference between evaluating a team and coaching a team. Evaluating generally entails pulling apart the performance, focusing on weaknesses and deficits, and reporting out on the shortcomings. Evaluation often has a negative connotation and involves limited to no support or coaching. Teachers will tell you they do not like the evaluation process. They use negative terms such as “gotcha,” “dinged,” “micromanaged,” “perfunctory,” and others to describe their experience with the teacher evaluation process. For special educators, the process is even more uncomfortable, as their daily work lives don’t often fit neatly inside of the box-checking process. Special educators have unique roles with outcomes that differ greatly from those of regular educators (e.g., IEP team meeting management, small group management, assessment, etc.). For this reason, the evaluation process can be even more painful and unhelpful.

Coaching, on the other hand, is all about the process of helping others get better. The connotation of coaching is positive and well met by educators. Coaching a team means looking for deficits and weaknesses, of course, but more importantly, it means teaching the players improvement and replacement behaviors that will lead to a win. Coaching is dynamic, specific to your role, engaging, and even fun; it is inspiring and transformative. Coaching is what new special education teachers need–not more evaluation boxes to check. They need real-time, detailed, supportive, and uplifting coaching that positions each of them for the win.

Coaching is inspiring and transformative. Coaching is what new special education teachers need–not more evaluation boxes to check. They need real-time, detailed, supportive, and uplifting coaching that positions each of them for the win.

Coaching is inspiring and transformative. Coaching is what new special education teachers need–not more evaluation boxes to check. They need real-time, detailed, supportive, and uplifting coaching that positions each of them for the win.

Technology and a New Paradigm

You might be thinking, “This all sounds well and good, but how can special education teacher coaching be done remotely?” Great question. If there is one thing the COVID-19 era has taught me, it is that we have extensive technologies at our fingertips for communication. Software such as GoToMeeting, Zoom, Ring Central, Skype, and others have given educators the capacity to live stream and communicate directly any time, anywhere. In addition, we have extensive capacity to simply record ourselves (via software, phone, or a laptop camera). All of this technology can be used to capture the role and activities of the remote special education teacher. If we are willing to embrace the technology that currently exists, there is no reason we can’t support teachers in their remote learning environments.

We can most certainly critique and coach the delivery of online content, in-person Zoom calls, interactive small group activities, etc. If we will only embrace a different paradigm and available technology, we can support special educators at a level never seen before. IEP meetings can be legally provided, run, and managed via virtual software. That meeting can be recorded and dissected, and direct coaching can be provided. In addition, there is a plethora of free “how to” videos on IEP writing, teaching, etc., on the web that can be curated and provided at no cost. All of the pieces exist; we just need to put them together.

Equity and Disproportionality

The concept of equity has arisen as a hot topic in the field of special education in the last few years. Primarily due to language added to the IDEA Act about disproportionality, states are now required to track placement and services to minority students during the special education process. States are tasked with ensuring that minority students are not found disproportionately eligible for special education services or overly disciplined. In short, the government wants to ensure equal distribution of services to students and also to limit any form of over-disciplining of minority students. For example, statistics indicate that African-American boys are disciplined more than twice as often as their white counterparts.

In a nutshell, the government wants to ensure equity of services and support. So what is equity? Different from the notion that everything should simply be equal, equity is about ensuring that all students get what they need individually. What might be best for Jameel might not be necessary for Scott. One area of considerable concern in relation to equity is instruction. Many special education students are currently working from home or in hybrid environments. Some students are getting in-class instruction, while others are limited to at-home support. All too often, the services at home do not equal the services at school. The virtual supports are “de minimis” at best. Therefore, it is essential that all students receive equitable instruction.

One way to ensure equity of instruction is to make sure at-home students have access to robust web-based instructional platforms. The platforms should be driven by an assessment process that produces quality diagnostic data and is linked to each child’s primary learning deficits. In addition, the system must have some type of formative assessment engine. It is crucial that educators be able to track the progress of students working from home. Without formative assessment data, educators are unable to pivot and make data-based instructional decisions. Equity of instruction is also about ensuring high quality content that meets the needs of each child.

Providing FAPE During COVID-19

It goes without saying that COVID-19 has presented special educators and school administrators with significant challenges. In the spring of 2019, educators were shocked when schools were completely shut down across the country. The Department of Education decided not to relax the regulations surrounding the IDEA. Therefore, special educators and school administrators had to figure out how to fulfill the requirements of IEPs that were written for school-based instruction. Many students went without instruction or received very limited instructional support that aligned with their IEP goals.

Going into the fall of 2020, some schools stayed open while others remained closed or used hybrid models. With more time to plan, schools have done a better job of providing students with services and supports at home. That said, the quality of instruction at home is not equal to that of in-school instruction, broadly speaking. Unfortunately for those at home, many schools have not taken advantage of technologies that both pinpoint specific student needs and align instruction to those needs. How then can schools provide Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE)?

COVID-19's Impact on Special Education

Roll over to seeReimagining Special Education with Technology

Educators are now leveraging technology to:

- Personalize instruction: Adaptive assessments and platforms tailor learning to individual needs.

- Bridge learning gaps: Targeted activities address specific deficits and accelerate progress.

- Engage students: Interactive resources make learning fun and motivating, even remotely.

- Track progress: Real-time data helps educators adjust instruction and ensure FAPE compliance.

Diagnostic assessment provided on an online platform and linked to virtual instruction can serve as a foundation for instructional services that comply with IEPs. Without utilizing this technology, schools are either offering vague instruction not aligned to student deficits or not offering virtual instruction at all. Not to provide virtual instruction to a child with an IEP learning from home is tantamount to refusing to implement the IEP. As all IEPs require SDI for each child based on his or her unique needs, schools must figure out ways to ensure quality, deficits-aligned virtual instruction.

Present Levels, Annual Goals, and Diagnostic Data

Although there are many areas of coaching that special educators and administrators need in order to fulfill both the spirit and the letter of the law, one area stands out. Arguably, there are few things more important in the special education process than developing a high quality, compliant, effective IEP document. Granted, there is much that goes into an IEP, and there are many people who contribute to the document. However, two areas are particularly important to in-class instruction and the services children receive. The core of the IEP document is composed of two sections: the present level (PLAAFP) and the annual goals. The PLAAFP — present level of academic achievement and functional performance — describes the child’s current performance in relation to both academics and functional pursuits. The PLAAFP for each child should present both strengths and weaknesses at a level that informs instruction.

The best PLAAFPs contain not just numeric but also qualitative data–for example, “Johnny can recognize numerators and denominators in fractions.” A good PLAAFP concurrently provides a robust and in-depth description of how the child is performing in school. The annual goals, on the other hand, are intended to provide guidance for the child’s educational program by establishing areas to focus on and clear goals and objectives within these areas. Frankly, the field of special education has a long way to go toward doing an exemplary job in these areas. Too often, vague and non-measurable statements are made.

IDEA Backgrounder

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act

Chapter 2 from Hulett, K. E. (2009). Legal Aspects of Special Education. Pearson Prentice Hall.

Facts at a Glance

- The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) is organized in a logical structure — Parts A-D — that has remained basically the same since its original enactment in 1975.

- Part A is titled General Provisions.

- Part B is titled Assistance for All Children with Disabilities.

- Part C is titled Infants and Toddlers with Disabilities.

- Part D is titled National Activities to Improve Education of Children with Disabilities.

- The IDEA defines special education as “Specially designed instruction at no cost to parents to meet the unique needs of a child with a disability” [pub.law number 94-142, section 602 (25)].

- Six elements of the IDEA constitute the law’s essential support structure. The individualized education program (IEP), the guarantee of a free appropriate public education (FAPE), the requirement of education in the least restrictive environment (LRE), appropriate evaluation, active parent and student participation in the educational mission, and procedural safeguards for all participants.

- The confidentiality regulations of the IDEA have their foundation in comprehensive legislation enacted by Congress in 1974 (the year before enactment of Public Law number 94-142) titled The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA).

As both a professional and a legal responsibility, special and general educators are expected to be conversant with what can be called the behavioral sequence:

(1) Determination that a behavioral intervention plan or BIP (positive behavioral intervention strategies and supports) is needed;(2) Development of the BIP, following a functional behavioral assessment (FBA); and (3) Implementation of the BIP with periodic review and modification, as needed.

It’s important to note that when discussing the IDEA as it pertains to daily practice in schools, leaders need not have an encyclopedic knowledge of the law, nor must they have the regulations committed to memory. As it pertains to special education, it is most important that leaders grasp the spirit and intent of the law. It is critical that leaders understand what Congress intended with the passage of the IDEA and how children are to be supported, protected, instructed, treated, and placed under the law. At any time during the school day, a leader can reference state regulations to look up timelines and other relevant information needed on a daily basis. That said, it is essential that leaders understand the meaning and practical implementation of such terms as Free and Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) and Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) as they support their special education teams and students day in and day out. The purpose of this chapter is to give the educational leader a solid understanding of the IDEA and its key principles–the single most powerful and critical law impacting students with disabilities today.

More than 45 years after the 1975 passage of Public Law number 94-142, now commonly known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), the objectives outlined in the law’s preamble remain essentially the same:

It is the purpose of the act to assure that all handicapped children have available to them … a free appropriate public education which emphasizes special education and related services designed to meet their unique needs, to assure the right of handicapped children and their parents or guardians are protected, to assist states and localities to provide for the education of all handicapped children, and to assess and assure the effectiveness of efforts to educate handicapped children. (Public Law No. 94-142, section 601).

Other than the term handicapped children — now superseded by children with disabilities — this declaration of purpose is still a valid and cogent statement of intent nearly a decade into the 21st century. This chapter will summarize the major elements of the IDEA.

Structure of the IDEA

The IDEA is organized in a logical structure — parts A-D — that has remained basically the same since its original enactment in 1975. Let’s take a look at that structure.

Part A, General Provisions

This part includes:

- findings and purposes;

- definitions of terms used throughout, such as “special education,” “native language,” “child with disability,” and “free appropriate public education”;

- requirements for employment of individuals with disabilities; and

- requirements for individualized family service plan (IFSP) and procedural safeguard mechanisms.

Part B, Assistance for All Children with Disabilities

This portion of the law contains the largest number of program requirements and represents the very core of the IDEA, including:

- matters related to fiscal policy and money management among federal, state, and local jurisdictions, including federal funding arrangements;

- responsibilities at the state level, usually directed to the state education agency; responsibilities of local education agencies, commonly meaning local school districts but also directed to other organizational units such as a collaboration of school districts for special education purposes;

- rights, protections, and responsibilities in the educational process, including evaluations, eligibility determinations, individualized education programs, and educational placements;

- procedural safeguards, also known as the due process provisions;

- federal administration and ongoing national data-gathering responsibilities of the states and local school districts; and

- preschool grants, directed to children three through five years of age.

Part C, Infants and Toddlers with Disabilities.

This is a national program that provides early intervention services for children from birth to age three who manifest or are at risk of developmental delay. This part includes:

- a definition of the eligible population;

- a list of authorized services;

- requirements for a statewide system in each state, and requirements for an individualized family service plan (IFSP) and procedural safeguard mechanisms.

Part D, National Activities to Improve Education of Children with Disabilities

This part, now including the Education Science Reform Act part E, comprises two major clusters of generally highly valued support programs — two of which (research and training of professionals) were created in the 1950s. These programs are administered at the national level, where awards are made to a wide array of eligible recipients in the form of grants, contracts, and cooperative agreements. The major components are:

- coordinated research and innovation;

- professional preparation;

- studies, evaluations, and ongoing national assessment of the IDEA’s effectiveness;

- parent training and information centers, including community parent resource centers;

- coordinated technical assistance and knowledge/information dissemination through regional resource centers, including institutes and clearing houses; and

- technology development and utilization of educational media services.

As part of the 2004 amendments, Congress transferred the research functions from the Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) to the Institute of Educational Sciences. The National Center for Educational Research, one of four centers under the institute’s umbrella, directly administers the IDEA’s research efforts.

Evolution of the Law

A review of the evolution of the IDEA requires attention to the programs authorized before public law number 94-142, as well as the numerous amendments that occurred after the law’s enactment in 1975 — although Public Law number 94-142 established the basic framework of rights and responsibilities that remains in place to this day. Pre-Public Law number 94-142 legislation helped develop an infrastructure of effective early intervention and special education practice while inaugurating a very modest but useful direct program managed at the state level. Post-Public Law 94-142 legislation attended to further requirements of the IDEA.

A bit of historical trivia aids in reducing the confusion commonly surrounding the titles used for the law. From 1970 to 1990, it was known as the Education of the Handicapped Act (EHA). In fact, Public Law 94-142 was actually a massive amendment, amounting to a “top to bottom” rewrite of the earlier core segments of the EHA. In the 1990 reauthorization of the EHA, Congress changed the title from the EHA to the IDEA. For the reader’s peace of mind, simply remember that the EHA became the IDEA, and this text will consistently lead with “the IDEA.”

What is a reauthorization? Put simply, Congress traditionally affixes an end date to a great many pieces of legislation; the action is popularly known as “sunsetting” the legislation. This means that Congress must revisit and “reauthorize” (or not reauthorize, depending on the circumstances) such legislation. Because policy makers agreed that Public Law number 94-142 constituted a bill of rights for children with disabilities and their families, part B of the IDEA was and remains permanently authorized (consult structure of the IDEA, beginning on page xx). However, parts, A, C, and D (definitions, early intervention and the national support programs administered at the federal level) require periodic reauthorization. Can part B still be amended at the periodic reauthorization of the other parts? Yes, but to make the point that part B constituted permanent civil rights legislation, the policy makers left part B unaltered for an unprecedented 20 years, except for minor refinements.

What follows is a brief history of the IDEA. The reader is advised that this segment represents nothing more than the evolution of the IDEA and does not address the universe of other national legislation — such as the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) — affecting the education of special education children. The Rehabilitation Act and the ADA are addressed later in this text.

Before Public Law No. 94-142

Cooperative Research Act of 1954, Public Law number 83-531

was the first federal research program in special education.

Training of Professional Personnel Act of 1959, Public Law number 86-158

was the initial federal program focusing on professional preparation for educating children with mental retardation[sic].

Teachers of the Deaf Act of 1961, Public Law number 87-276

trained educational personnel for hard of hearing and deaf children.

Mental Retardation Facilities and Community Health Centers Construction Act of 1963, Public Law number 88-164

expanded support for professional preparation to teach a wider population beyond mental retardation and further expanded the research program.

was passed in 1965 as an amendment to Title 1 of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA); it was the first major direct program supporting the education of children and youth with disabilities; it stood as the largest fiscal program for instruction until Public Law 94-142, with the assistance primarily directed towards state-run institutions and schools.

Elementary and Secondary Education Act amendments of 1966, Public Law number 89-750

created the Bureau of Education for the Handicapped (BEH), which later became the administering agency for the EHA and the IDEA. The agency was later titled the Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP), which still exists today.

Elementary and Secondary Education Act amendments of 1967, Public Law number 90-247

was the first national commitment to technical assistance and dissemination, with the creation of centers for deaf-blind children in response to the rubella epidemics of 1964; it also created regional resource centers (RRCS) for special education.

Handicapped Children’s Early Education Assistance Act of 1968, Public Law number 90-538

authorized the first early childhood model programs focusing on children ages three through nine, but emphasizing the pre-school years for children ages three through five.

decoupled special education programs from the ESEA and consolidated them in a separate and independent EHA.

Education Amendments of 1974, Public Law number 93-380

is considered the “early warning” legislation for Public Law number 94-142; it required full-service goals and timetables, as well as assurances that such elements as due process and least restrictive placements were in development; it set no dates for actual implementation, however.

Public Law 94-142

Education for All Handicapped Children’s Act, Public Law number 94-142

is the landmark legislation requiring a free and appropriate public education for all children with disabilities — the heart of which is contained in parts A and B of the IDEA.

After Public Law number 94-142

Education of the Handicapped amendments of 1977, Public Law number 95-49

extended authority for the discretionary programs and eliminated the National Advisory Committee on the Handicapped.

Education of the Handicapped Act amendments of 1983, Public Law number 98-199

strengthened the support programs under part D (grants and contracts managed and awarded at the national level) to promote integration of children with severe disabilities, including creation of severely handicapped institutes; it also promoted transitions from school to adult living and a change in state-wide service systems, and required least restrictive environment as well.

Handicapped Children’s Protection Act of 1986, Public Law number 99-372

reversed the US Supreme Court decision requiring an exhaustion of the IDEA due process procedures before filing a civil action under any other statute, such as section 504; it also authorized an awarding of attorney fees to the prevailing party and administrative due process if approved by a court.

Education of the Handicapped Act amendments of 1986, Public Law number 99-457

completed the age mandate of Public Law number 94-142 by establishing a phase end of FAPE for pre-school children three through five years of age under part B; created an early intervention program for infants and toddlers from birth through three years of age, now part C; also authorized a state-of-the-art program for technology and for educational media and materials.

Education of the Handicapped Act Amendments of 1990, Public Law number 101-476

added transition services to the required content of the Individualized Education Program (IEP), which was viewed only as a statutory clarification of an existing requirement; added traumatic brain injury and autism to the disability categories; changed the name of the EHA to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA); and established the Parent Training and Information Center (PTIC) system on a nationwide basis.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act amendments of 1997, Public Law number 105-17

opened part B to needed adjustments more than 20 years after the enactment of Public Law number 94-142; included major refinements that strengthened the relationship of the general curriculum, overhauled the evaluation and re-evaluation provisions, added new stipulations in the IEP regarding state and district-wide tests, and designed controversial procedures related to behavior and discipline.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Amendments of 2004, Public Law number 108-446

coordinated the policy and procedures of the IDEA with those of the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB); further amended the eligibility procedures, IEP requirements, and procedural safeguards; streamlined discipline procedures; and consolidated special education research with the other federal research in the Institute of Education Services.

Special Education

In the definitions of diagnostic categories given in the IDEA regulations, the reader should note the use of the phrase “that adversely affects a child’s educational performance.” Further, the statutory definition of a child with a disability reads: “…. and who, by reason thereof, needs special education and related services.” These two clauses are critical for determining 1) precisely which children will be served under the IDEA, and 2) precisely what makes this educational program different from the general education program.

The IDEA defines special education as “specially designed instruction, at no cost to parents, to meet the unique needs of a child with disability” [Public Law number 94-142, section 602(25)]. The IDEA regulations, published in the Code of Federal Regulations, or C.F.R, further define specially designed instruction to mean “adapting as appropriate to the needs of an eligible child under the part, the content, methodology, or delivery of instruction to address the unique needs of the child that result from the child’s disability” [34 C.F.R. Section 300.39(B)(3)].

Policymakers in both Congress and the administering federal agency have not further defined special education in the IDEA. Wisely, they continue to respect the idea that the parameters of special education are a professional matter that continually evolves through professional research, training, and advances in practice. What they do say through the IDEA, however, is that special education must be provided to a defined group of America’s children.

The Six Pillars of IDEA

Six elements of the IDEA constitute the law’s essential support structure, and no single element is complete without the presence of the other five. These six elements are the Individualized Education Program (IEP), the guarantee of a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE), the requirement of education in the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE), appropriate evaluation, active participation of parent and student in the educational mission, and procedural safeguards for all participants.

Individualized Education Program (IEP)

The cornerstone of educational planning and implementation under the IDEA is undoubtedly the requirement of individualized programming for each student. In fact, the creation of such a legal requirement in 1975 may be viewed as nothing less than one of the most ambitious actions ever undertaken in federal education policy.

The mechanism for delivering this requirement is known as the Individualized Education Program, or IEP. Either an IEP or its early childhood equivalent, the Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP), must be in place and operating for every child designated as eligible for services under the IDEA. The IEP has been, and will continue to be, both the cornerstone of the IDEA and the heart of American special education.

The statute says simply, but with powerful implications, that “the term ‘Individualized Education Program’ or ‘IEP’ means a written statement for each child with a disability that is developed, reviewed, and revised in accordance with this section” [Public Law number 94-142, section 614(D)(1)(A)]. The law then specifies 1) the required content of each child’s IEP, 2) how parents will receive progress reports, 3) who must, and who may, be included in the IEP teams, 4) considerations in the development of the IEP, including certain special factors, 5) the role of the regular education teacher, and 6) thorough requirements for review and revision of the IEP. The regulations repeat the law, expanding and clarifying where necessary. Chapter 10 of the text is devoted to a comprehensive discussion of the IEP with practical implications and recommendations.

Free and Appropriate Public Education (FAPE)

A fundamental, non-debatable presumption embodied in the IDEA is that no child can be denied a public education. This is popularly known as the principle of zero reject. Regardless of the severity of disability, each and every child has the right to a public education. In fact, the groundswell of citizen advocacy in the late 1960s and early 1970s that led to the zero reject principle was known as the “right to education” movement. Further, the IDEA states that the educational program for eligible children cannot be just any program of public education; it specifies that the program must be special education appropriate for the individual child.

The law’s definition of free and appropriate public education, or FAPE, is lean in terms of words but robust in terms of implications: the term “free appropriate public education” means special education and related services that a) have been provided at public expense, under public supervision and direction, and without charge; b) meet the standards of the state educational agency; c) include an appropriate preschool, elementary, or secondary school education in the state involved; and d) are provided in conformity with the Individualized Education Program under Section 614(d) [Pub. L. No. 94-142, § 602(9)]. The statute guarantees a FAPE and the corresponding actual availability of a FAPE to an eligible child for as long as necessary from the child’s third birthday through his or her 21st year, with certain qualifications such as matriculation with a regular high school diploma. Chapter 7 explorers all facets of FAPE.

Least Restrictive Environment

Another non-debatable presumption at the core of the IDEA is least restrictive environment, or LRE. Put simply, LRE requires that children with disabilities be educated in the same place as all other children. The various terms have enjoyed currency since the enactment of Public Law 94-142 in 1975 — including integration, mainstreaming, inclusion, full inclusion, and least restrictive environment — but none has precisely the same meaning. Regardless, each of the terms embodies the bedrock belief established in the US Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), namely that separate is unequal, as well as the converse: that together is inherently better. Parenthetically, the expression “least restrictive environment” has appeared in the regulations since they were first promulgated in 1977 and thus has the effect of law.

Although the IDEA states that children with disabilities must be educated with children who are non-disabled, it also includes a critical qualifier: “to the maximum extent appropriate.” What does that mean? The law offers a specific answer: “that separate classes, separate schooling or other removal of children with disabilities from the regular educational environment occurs only if the nature or severity of the disability is such that education in regular classes with the use of supplementary aides and services cannot be achieved satisfactorily” [Pub. L. No. 94-142, § 612(a)(5)].

One can describe this critical qualifier as a necessary — though often frustrating — tension between two desirable objectives for children with disabilities. On one hand, maximum inclusion of the child is mandated; on the other hand, an educational program that meets the child’s needs may require some degree of separation from the educational environment shared by all students.

So, how is this tension resolved? The law leaves the resolution to the IEP team, which includes the parents. Once an agreement is reached, the placement for the child becomes, by definition, the least restrictive educational environment for that child. Therefore, pull-out periods in a resource room coupled with regular classroom placement may be the LRE for one particular child, while instruction in a separate class may be the LRE for another child. Professionals must bear in mind that when the IEP is being developed, the presumed placement must be the regular classroom with full inclusion in all other school activities.

To the extent that this is not what is agreed on in the final IEP, that document must include an explanation of what options were considered and why something less than full-time inclusion in the regular setting was chosen. A comprehensive treatment of LRE, including the continuum of placement options, is available in Chapter 8.

Appropriate Evaluation

The evaluation is the process through which a child is determined to have a disability requiring the support of special education-related services. The evaluation process should also help identify the child’s actual special education and related service needs, though the evaluation precedes the development of the IEP. A team of qualified professionals and the child’s parents must make the final eligibility determination. The IDEA sets out many critical requirements for conducting an evaluation. These requirements, designed to protect against misidentification, include the use of a variety of assessment tools and strategies, a prohibition against the use of any single procedure as a sole criterion, assessment of the relative contribution of cognitive and behavioral factors in addition to physical or developmental factors, and protections against evaluation instruments that may be racially or culturally discriminatory.

The issue of nondiscriminatory testing and evaluation was the central concern in the original evaluation component of Public Law 94-142, and given the ever increasing number of immigrants in the United States from non-English speaking countries since the law’s original enactment, the concern surrounding this issue have grown. Once again, the rule that is fundamental throughout the IDEA applies to evaluation: namely, evaluation must be appropriate for determining the needs and strengths of each child on an individual basis. A full discussion of evaluation and re-evaluation is offered in Chapter 9.

Parent and Teacher Participation

Central to the design and functioning of the IDEA — indeed, central to the success of special education throughout its history — is the family-professional partnership. Family, of course, means the child and the child’s parents, and professional means the teachers and other individuals who apply their expertise to the child’s education. The activities that occur daily in schools when parents and professionals partner in the learning enterprise for individual children are reflected at a distance in national politics. Parents were indispensable in obtaining passage of Public Law 94-142, and they remain vigilant guardians of both the content and the implementation of the IDEA to this day. The section of the law addressing procedural safeguards focuses primarily on protecting the educational rights of both children and their parents. If the law seems to some critics too heavily weighted toward parents, supporters argue that the single family unit would be at a distinct disadvantage in relation to public authorities and public school systems without such a deliberate tilting of the scales.

Beyond procedural safeguards, the law guarantees the right of consent to and participation in every aspect of the educational process, including evaluation and re-evaluation, placement, the IEP, and the use of public and private insurance. The same aspects of guaranteed participation apply — where deemed appropriate — to the student, with involvement in the development of the IEP being a prime example. As a matter of law, the schoolhouse door is open wide to parental involvement. The importance of parental involvement is addressed throughout this text.

Procedural Safeguards

The right to procedural safeguards, also known as the right to redress of grievance and the right to due process of law, has a very long history; it dates back to early medieval English common law and was eventually carried forward into the US Constitution’s Bill of Rights. The guarantee of procedural safeguards appeared early in the development of the nation’s special education law because such guarantees were required first by the courts in two historic 1970 “right to an education” decrees. The pair of rulings — Pennsylvania Association for Retarded Citizens vs. Pennsylvania (1972) and Mills v. Board of Education of the District of Columbia (1972) — greatly influenced both the creation and the content of the procedural safeguard section of Public Law 94-142.

The opening lines of the IDEA’s procedural safeguard section make a frank statement of purpose: “to ensure that children with disabilities and their parents are guaranteed procedural safeguards with respect to the provision of free appropriate public education” (Public Law 94- 142, § 615). The law lists a number of essential guarantees, including the right to examine all educational records, the right to have an impartial hearing and an impartial hearing officer, the right to receive certain prior notices, the right to be afforded mediation, the right to be accompanied by an attorney, and the right to have a state-level appeal if a hearing has been conducted by a local education agency.

Relating to the highly charged issue of discipline infractions, this section of the IDEA also contains protections for all parties — parents, students with and without disabilities, and school personnel — in an effort to balance the critical need for school safety with the right of a particular child with a disability to a continuing educational program. Although the IDEA’s procedural safeguards are focused primarily on providing protections to children and their parents, the reader should understand that these safeguards also benefit school systems, teachers, and other school personnel because the essence of due process is the right of all parties to make their case in an impartial setting. An examination of the concepts and dimensions of procedural safeguards is found in Chapter 11.

Confidentiality of Information

Along with the six pillars of the IDEA, other issues merit attention, including the matter of strict confidentiality of personally identifiable information. In keeping with section 612(a)(8) and 617(c) of the IDEA, the implementing regulations make it clear that “the state must have policies and procedures in effect to ensure that public agencies in the state comply with sections 300.610 through 300.626 related to protecting the confidentiality of any personally identifiable information collected, used, or maintained under Part B of the act” (34 C.F.R. Section 300.123).

The foundation of the confidentiality regulations of the IDEA is the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA). Enacted by Congress in 1974, the year before the enactment of Public Law 94142 under the sponsorship of US Senator James Buckley, FERPA effectively mandates privacy protections for all of America’s school children and their families.

As with the IDEA, FERPA’s basic requirements remain the law to this day. Given the frequently sensitive and far reaching information gathered about them, no group of children and their families is more in need of a strict code of privacy than students who are receiving or being considered for eligibility to receive special education services and their parents.

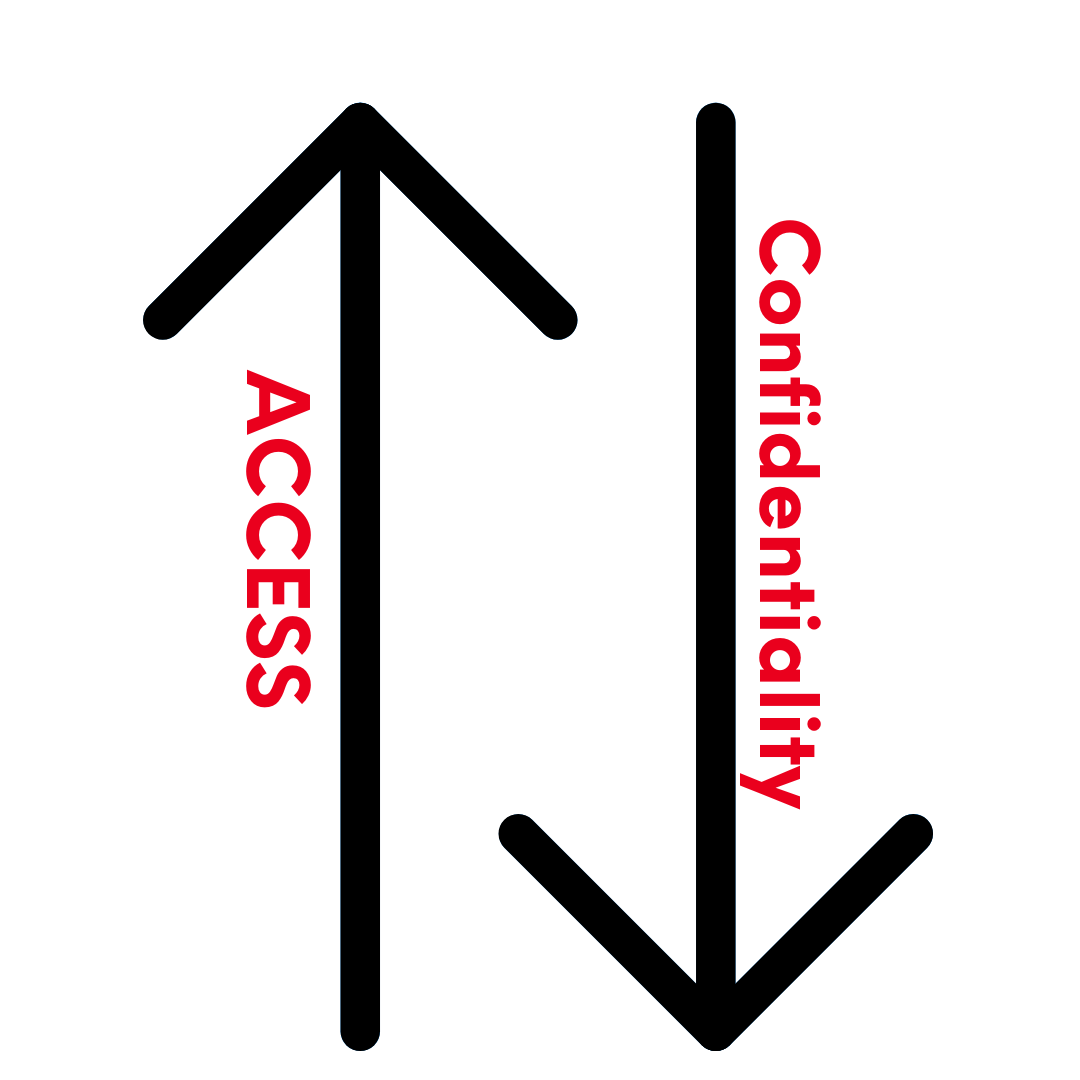

Upon close scrutiny, the confidentiality provisions are actually a delicate balance of two necessary protections — access and confidentiality. Let’s first turn to the issue of the right of access. The regulations state that each participating agency must permit parents to inspect and review any educational records relating to their children that are collected, maintained, or used by the agency under this part. The agency must comply with a request without unnecessary delay and before any meeting regarding an IEP, or any hearing pursuant to Section 300.507 (overall due process) or Sections 300.530 through 300.532 (discipline procedures), or a resolution session pursuant to Section 300.510, and in no case more than 45 days after the request has been made (34 CFR section 300.613).

In support of a parent’s right to inspection and review, the agency must respond to reasonable parental requests for explanations and interpretations; provide copies of the records when failure to do so would, in effect, deny the right to inspect; and allow the parents or their representative to inspect and review the records. What about the information itself? Every state education agency must have available to the public its policy regarding information gathered about students. This policy should include a description of the children about whom personally identifiable data are maintained; the type of information; the methods the state intends to use in gathering information, including the sources from whom information is gathered; and the use to be made of the information.

All of the local education agencies (school districts) in the state must adhere to the state policy (see 34 CFR Section 300.612). When considering personal information gathering in this context, a good rule of thumb is this: the only information gathered should be that which is needed to provide appropriate special education-related services to the child.

Now we proceed to the matter of confidentiality. While parents and authorized personnel from the school district generally have access to student information, for all other persons and parties access is greatly restricted. As a general rule, parental consent must be obtained before personally identifiable information is shared with anyone other than authorized personnel and, importantly, before the information is used for any purposes other than those specified under the IDEA. Further, each agency must keep a careful record of any other party who is given access, including the individual’s name, the date when access was authorized, and the purpose for which access was authorized.

An important, but too often overlooked, stipulation in the federal IDEA regulations addresses the destruction of information. Because of the critically precise wording, the regulation is quoted below.

Destruction of Information

The public agency must inform parents when personally identifiable information collected, maintained, or used under this part is no longer needed to provide educational services to the child. The information must be destroyed at the request of the parents. However, a permanent record of a student’s name, address, and phone number, his or her grades, attendance record, classes attended, grade level completed, and year completed may be maintained without time limitation (34 CFR Section 300.614).

Importantly, the confidentiality regulations include due process procedures. Here’s the trigger: “A parent who believes the information and the education records collected, maintained, or used under this part are inaccurate or misleading or violate the privacy or other rights of the child may request the participating agency that maintains the information to amend the information.” The agency may then agree to amend the information or refuse to do so. If the agency refuses, it must inform the parents and provide an opportunity for a hearing.

If, after a hearing, the agency still refuses to amend the information, it must allow the parents to place in the child’s records a “statement commenting on the information or setting forth any reasons for disagreeing with the decision of the agency.” This parental statement must be maintained in the child’s records and be made available if the record or the contested section is disclosed to any party (34 CFR Sections 300.618 – 300.621).

Ideally, full blown due process concerning educational records should rarely be required because parents and schools can amicably amend the records. Nonetheless, the heightened attention to discipline infractions over the past 20 years suggests that all parties must be aware of protections and procedural safeguards in matters involving personally identifiable data. When evaluating access to and privacy of information in a particular case or locale, the reader is cautioned to investigate the precise policy and practice of the specific state or school district due to the possibility of loopholes and insufficient monitoring. The complete provisions of confidentiality may be found in the IDEA regulations at 34 CFR Section 300.610 — 300.627.

Transition Services

The 1997 amendments to the IDEA added requirements for transitioning disabled students to life after school. Specifically, the IDEA states, as a goal, its intent “to ensure that all children with disabilities have available to them a free appropriate public education that emphasizes special education and related services designed to meet their unique needs and prepare them for employment and independent living” [Public Law Number 105-17, Section 601(d)]. Although access to education is its own end under the law, the supreme goal of the IDEA and special education is clearly preparation for self-fulfillment in the adult years.

Accompanying the IDEA regulations, a notice of interpretation includes a statement borrowed from other legislation that is a powerful rendering of the post-school objective for students with disabilities. Section 701 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 describes the philosophy of independent living as encompassing consumer control, peer support, self-help, self-determination, equal access, and individual and system advocacy in order to maximize leadership, empowerment, independence, and productivity of individuals with disabilities and enable the integration and full inclusion of individuals with disabilities into the mainstream of American society (IDEA Regulations, Appendix A, IEPS, III).

In requiring that a student’s IEP include a transition component, the IDEA stipulated until 2004 a two-tiered approach: one commencing when the student turned 14 and the second when the student turned 16. However, the law stated that in both cases the program could begin at a younger age if the IEP team considered it appropriate. The requirement at age 14 emphasized transition services that focused on courses of study, such as participation in advanced placement courses or a vocational education program. The requirement at age 16 was much more focused on practical outcomes and included the critical requirement that non-education agencies, where appropriate, be involved in the provision of services. State vocational rehabilitation agencies and state employment and training agencies are obvious examples of such agencies.

The movement to mandate full-blown transition services at age 14 acquired special urgency because of the still disturbingly high dropout rate among students receiving special education services. In fact, experts argued that starting transition services for students with disabilities at age 14 (or earlier) constituted sound policy for three pragmatic reasons: 1) “The sooner, the better” makes eminently good sense for all students who have special challenges that may last throughout their lifetime. 2) If these students should still drop out, hopefully they will leave with useful life skills gained at a relatively early time. 3) Because of meaningful, future-oriented transition services, these students are more likely to be motivated to complete their education, obviously a more highly desired outcome than the preceding item.

However, in a move broadly condemned as a giant step backward, the 2004 IDEA amendments moved the age of initiation of transition services to 16. This significant setback occurred during Senate and House negotiations to produce a final joint bill. Even though the House bill had included services at both 14 and 16 and the Senate bill had required the initiation of all transition services at 14, 14 was stricken and 16 was inserted into the final bill without comment or justification from the conferees. The student’s participation in the IEP meeting is not an apparent or professional option when the IEP team is considering transition services. The regulations require that the student be invited, regardless of age. If the student does not attend the IEP meeting, the education agency “must take other steps to ensure that the child’s preferences and interests are considered” [34 CFR section 300.321 (B)].

Having been developed and refined over two decades, the IDEA’s definition of transition services offers a reliable and useful summary for the practitioner. The term “transition services” means a coordinated set of activities for a student with a disability that (A) is designed within an outcome-oriented process, which promotes movement from school to post-school activities, including post-secondary education, vocational training, integrated employment (including supported employment), continuing and adult education, adult services, independent living, or community participation; (B) is based upon the individual student’s needs, taking into account the student’s preferences and interests; and (C) includes instruction, related services, community experiences, the development of employment and other post-school adult living objectives, and, when appropriate, acquisition of daily living skills and functional vocational evaluation [Public Law 105-17, section 602 (34)].

Consideration of a student’s behavior under the IDEA is most often associated with the controversial discipline procedures added to the due process section of the law in the 1997 reauthorization. Too frequently overlooked, however, is the addition of an important requirement focused on behavior consideration and the development of IEPs for all children eligible for special education services. Under the heading of “Consideration of Special Factors,” the law stipulates that the IEP team must, “in the case of a child whose behavior impedes his or her learning or that of others, consider, if appropriate, strategies, including positive behavioral interventions, strategies, and supports to address that behavior” [Public Law number 105-17, section 614 (D) (3) (B)].

Further, if the IEP team decides strategies like the ones outlined in the law are necessary, a statement to that effect must be included in the child’s IEP. Not only is behavioral intervention a crucial component of support for the child, but it also provides a potentially important protection for the other students in an inclusive learning environment. Early behavioral intervention may, in actuality, provide an “ounce of prevention” against future behavior problems. Another important reason for utilizing early behavioral interventions is the possibility that failing to do so may be a violation of FAPE.

Overall, the behavioral intervention requirement is meant to promote the participation of the child and the regular education environment as opposed to a more restrictive setting. That stipulation is an important safeguard in the guarantee of LRE for the child is amply reinforced by another statutory mandate that regular education teachers participate in determining appropriate positive behavioral interventions and strategies as members of the IEP team. (Public Law number 105-17, section 614 (D) (3) (C)).

Finally, including behavioral strategies — again, only if appropriate — may be an important protection for the child if there should later be a disciplinary infraction resulting in the need to determine whether the behavior was a manifestation of the child’s disability. As a result of both growing concerns over school safety and improved research and behavioral interventions for special needs children, two terms have permanently joined the lexicon of special education: functional behavioral assessment (FBA) and behavior intervention plan (BIP).

Deferring to the expertise of the professionals, Congress and the administering agency have not defined these terms. Nonetheless, the law expects the states, as part of their ongoing professional development programs, to “enhance the ability of teachers and others to use strategies, such as behavior interventions, to address the conduct of children with disabilities that impede the learning of children with disabilities and others” [34 CFR section 300.382 (F)].

Thus, as both a professional and legal responsibility, special and general educators are expected to be conversant with what might be called the behavioral sequence, which includes: 1) determination that a BIP, which encompasses positive behavioral intervention strategies and supports, is needed; 2) development of the BIP, following FBA; and 3) implementation of the BIP, with periodic review and modification, as needed.

Under the IDEA, the federal government holds each state responsible for full compliance by all parties within its jurisdiction. The law requires that states engage in active monitoring and enforcement in all of their school districts and other participating entities. States are required to keep a written record concerning their policies and procedures related to the IDEA. These policies, which must be available for public review, are most likely to be housed in the special education division of the state education agency. Many of these documents are available on state education agency websites. Correspondingly, the US Department of Education actively monitors the states for continuing compliance. The monitoring of state IDEA compliance is typically done by the agency’s Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP), which is housed within the larger Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services (OSERS).

State monitoring typically occurs on a rotating basis. It involves onsite visits by federal personnel and often includes public hearings, which can be highly valuable in discovering compliance shortcomings. OSEP advises states of any gaps in compliance, and those states that are out of compliance are expected to design a corrective action plan with a timetable for revisions and modifications. The law requires full transparency to the public in all aspects of the monitoring process, meaning that any document declared “classified” or any denial of access to information should be treated suspiciously.

Summary

The IDEA’s essential features have remained remarkably stable and unaltered in the 40 years since the original enactment of Public Law number 94-142. Structured in four parts (A-D), the law combines a bill of rights for children with disabilities and their families with provisions for federal fiscal support. In addition, the IDEA provides educational and other management directives to all levels of school governance along with ongoing infrastructure support that is administered at the national level. The law delineates the characteristics of the eligible population of children to be served, as well as the nature of the services to be provided. The law contains six elements that represent the pillars of the IDEA, as well as American special education as a whole. Beyond these six elements, other features such as confidentiality, transition, and behavioral provisions warrant careful attention and study.

Critical thinking questions:

- How did this review of the IDEA compare with your prior perceptions of the IDEA?

- Does the law strike you as unduly complex and prescriptive? If so, why?

- In your experience, are there requirements in the special education regulations at the state and local levels that are not the result of the IDEA, though you thought they were? What are they?

- Would you change any of the fundamental features of the IDEA as we advance into the 21st century? If so, what would you change and why?

- Would you change any features of the IDEA regulations that were presented in this chapter? If so, what would you change and why?

- What do you think would be the effect if the IDEA were totally repealed tomorrow?

- If you’re a teacher or other professional working in public education, which requirements of the IDEA and its accompanying regulations do you find most helpful? Which are least helpful? As a professional, what changes would you recommend in your own working environment to make the IDEA more effective for everyone?

Bibliography

- Common Educational Tests Used for Assessments for Special Education. https://dredf.org/special_education/Assesments_chart.pdf

- IDEA Act. https://sites.ed.gov/idea/

- Ten Steps in the Special Education Process: https://www.readingrockets.org/article/10-steps-special-education-process

White Papers

- An Inclusion Learning Model

- Students Are More than Single Scores: Adopting a Diagnostic Approach to Assessment

- Four Ways to Avoid Legal Disputes